How to Tell If Your Contractor is Good

Here's how we vet contractors, and ensure high-quality installations.

A lot of HVAC salespeople will try to convince you to pay more money for “quality”, but won’t have an answer when you ask them what that means.

Today, we’ll show you what it means. Here are the things we check for at Laminar Collective when we aim for high-quality installations.

Sizing & Equipment: is the heat pump sized correctly in the first place?

Design & Aesthetics: good line set runs and/or ductwork that make sense?

Technical Competency: is the heat pump installed correctly?

Permits: do they pull permits, particularly electrical?

Service & Reliability: are they nice? Do they respond to calls & email?

Sizing & Equipment Selection 📐

Get a Manual J report if you can. We do one for every house. Practically, you should ask the person who does a walkthrough what they’re doing to ensure proper sizing.

The goal of this step is to avoid oversizing the equipment relative to the size of your house. Oversizing is like buying a Ferrari to drive to the grocery store: you don’t need it, and it can actually drive up your electricity bills.

Contractors typically will run a report called a Manual J to calculate heat load. They may use a tool such as:

You should get a heating and cooling load. Here’s how it looks for a triple decker:

Unit 1

Heating 18,000 BTU

Cooling 10,000 BTU

Unit 2

Heating 16,000 BTU

Cooling 9,000 BTU

Unit 3

Heating 26,000 BTU

Cooling 11,000 BTU

12,000 BTU = 1 ton, which should inform you of the size of your condenser. Most modern inverter (variable speed) systems have an upper & lower range of output. Your goal is to make sure that the heating & cooling performance of the proposed equipment is as close as possible to your heating & cooling needs as possible.

For example, here’s a Mitsubishi 3-ton, 4 zone condenser:

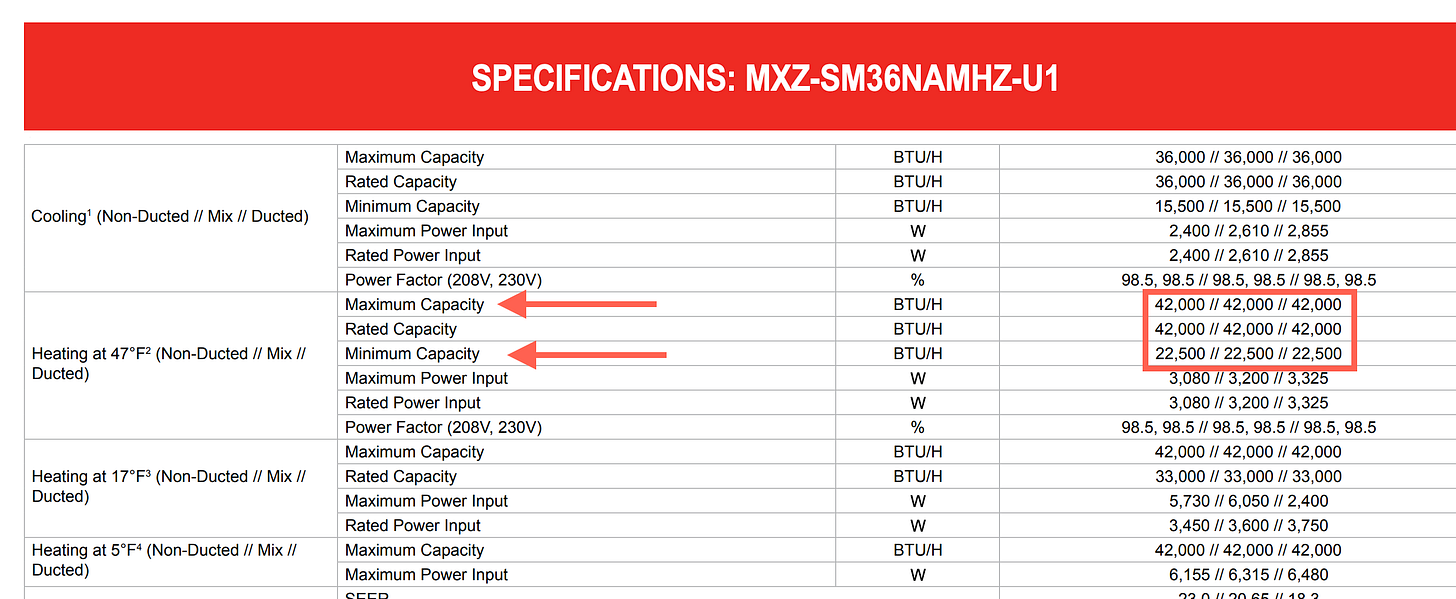

And here’s its specifications (submittal) sheet:

With a minimum capacity of 22,500 BTU, this condenser would make for a poor fit for the 1st floor unit up there, which only requires 18,000 BTU.

In some cases, we have seen 4-ton systems recommended for a house that only needs 2-tons. Yeah, that’s bad sizing right there.

You can read all about the triple decker example above, with equipment analysis, here:

Ductwork Design

IF you have pre-existing ductwork:

One of the biggest design question we face in LC installations is whether you can reuse the ductwork or not. Maybe you have central air with an AC. Maybe you have a furnace that connects to ductwork.

Say no more. We wrote an entire guide on that:

It more or less comes down to

How big is the space you need to heat/cool?

How much air do you need to heat & cool it?

Can you move that much air through the ductwork without making the fan push way too hard & burning out the motor?

Is all the air leaking through the ducts in like, your basement/attic?

Please confirm with an in-person walkthrough with an experienced tech before the actual installation. The biggest risk is ductwork that is too small or has way too many bends, because then it’s hard to move air through the ducts and that leads to poor airflow & high duct pressure (e.g. fan motor burning out).

This usually happens when ductwork is sized only for heating1, and we’ve seen this a bit less when it comes to ductwork sized for both AC and heating.

Our recommendation: get a duct evaluation, if you have an older duct system, per our guide above. If it doesn’t pass the test, make sure you have someone experience who can make the modification required.

⚠️ Note: if you have a Cape House, design can be significantly more difficult via. ducted. ⚠️

IF you don’t have ductwork at all:

Congratulations, you may be in a better spot. You could get ductless wall units in each room, or you could opt for ducting in the attic & ductless on the 1st floor, if you’re in a standard colonial SFH. This is a bit easier, but you also may want to consider…

Line Set Design & Aesthetics

This is where you should ideally ask for past references. How are the exterior line covers? How are the interior line runs? Is the contractor good at hiding interior line runs in the basement / up closet space?

This is good:

This is bad:

Line runs are generally easier to do for buildings that have straight, unobstructed side walls. They tend to be more difficult in buildings that have some sort of exterior soffit that obstructs a straight run, like this one:

If you’re in a house with Victorian features, ask for visual references. You’ll want to be sure that the contractor knows what they’re doing. This also happens a lot for duplexes, particularly for the top floor.

On the inside, good installations will pretty much hide all line set, meaning that you’ll only see the wall units. Like so:

Generally, we aim to work with contractors who have exhibited a history of good line set design. This is a basic skill, and you need it for every single type of installation.

Technical Competency 🔧

Here are 2 incredibly common reasons heat pumps fail:

Refrigerant leaks / impurities (all systems)

Compressor / fan breaking down (ducted systems)

To reduce the risk of this happening, ensure contractors properly account for: leak detection, and duct pressure/sizing.

1

Leak detection - if the refrigerant that carries the heat in the heat pump leaks out, your system stops working (or takes a big performance hit). You can ensure this doesn’t happen with a pressure decay test, and by pulling a deep vacuum.

Best part is? You can literally watch the installation techs do this. IF THEY DON’T DO IT, DON’T PAY THEM.

Here is a guide that explains how this works in super simple parlance:

It bears repeating.

IF THEY DON’T DO THIS, DON’T PAY THEM.

1.5

Eliminating impurities - HVAC guru Nate Adams puts it best:

New refrigerant lines still have some contamination in them (water is a contaminant to refrigerant). The best way to get it out is to put it in a deep vacuum. Atmospheric pressure is about 750,000 microns. You for sure want to get below 500, preferably below 100 microns. That vaporizes contaminants and sucks them into the vacuum pump.

Brazing with nitrogen - if you’re brazing, soot from brazing can add a lot of acid in the refrigerant which can substantially reduce compressor life. It's a simple fix: flow a few psi of nitrogen while brazing so soot can't get into the connections.

2

Low duct pressure - if you’re installing a ducted system, the pressure inside the ducts (static pressure) should be as low as possible for fan life, compressor life, and coil life. The two easiest ways to reduce it are to downsize the equipment and to upsize the ductwork that connects to the unit, both supply and return. We talk about this in our ductwork performance testing article.

Huge thanks to HVAC expert Nate Adams, whose material I paraphrased. Our full conversation is in the Appendix2 section.

Permits and Inspections 🔦

Pull an electrical permit. Every town we called said you should pull one.

Ductless:

Ducted:

If there’s one thing you should check, it’s the electrical. Make sure it’s done right.

Unfortunately, cities also sometimes make it difficult to schedule inspections, as I talk about here in our letter to Mass Save. Nonetheless, you’ll still want it done so you know the installation is up to code.

Service & Reliability

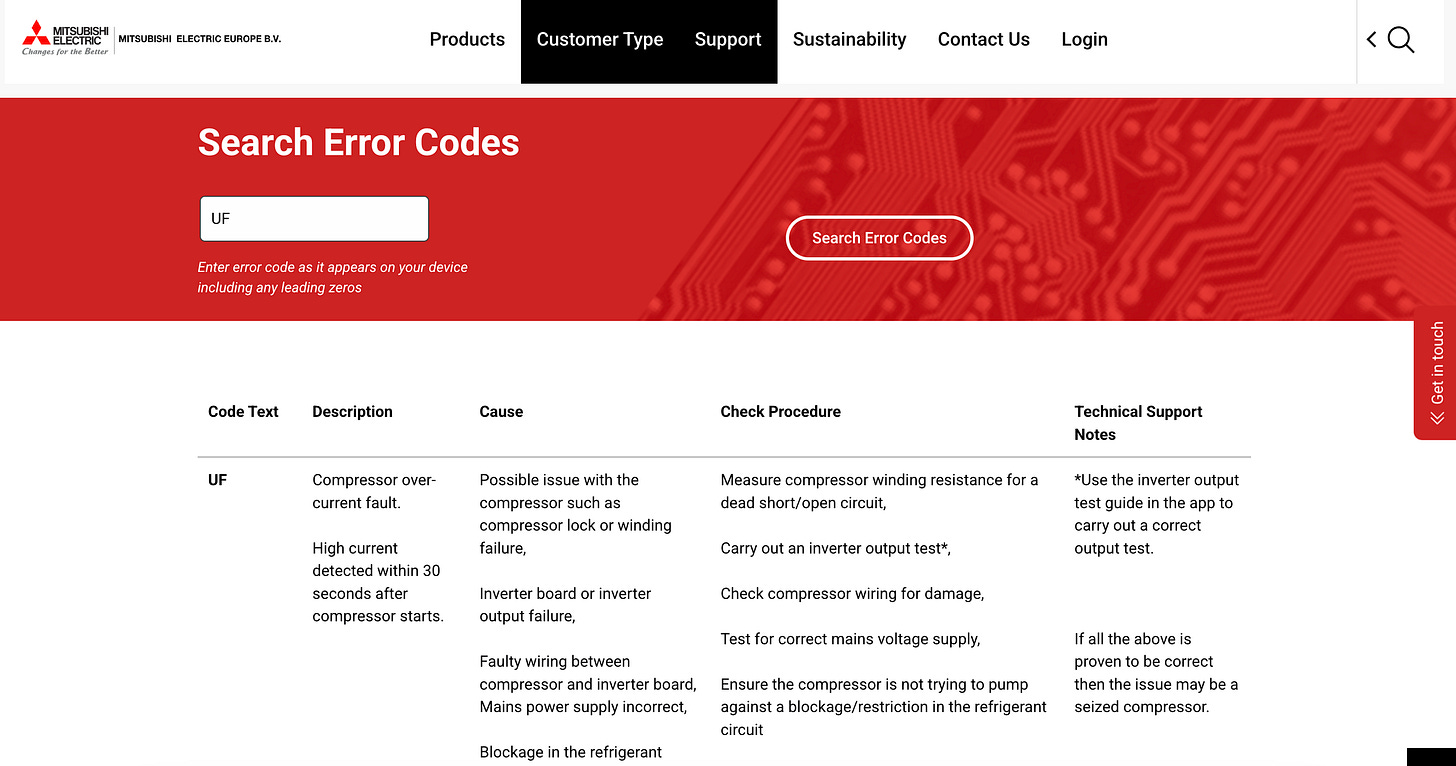

When something breaks, there’s typically an error code. You can expect to go to a website like this one to search up what the error codes are, and what to do:

Determining whether a contractor has a high level of service depends on

How familiar they are with the brand they are installing & the error codes

Technical support & parts availability from the manufacturer

How much resource they allocate to service

Familiarity: I think you’ll want to go with a contractor who, obviously, have lead installation techs or service technicians who have been in the field long enough to have seen (and fixed) a bunch of problems on service calls.

Tech support: Mitsubishi is actually great, in this regard. Like, we’ve called the hotline ourselves before, and they know what they’re talking about. I anticipate this edge to fade away in about a year, particularly as the heat pump market matures; by late 2025, I anticipate most mini-split systems to more or less be the same3.

Parts availability: Likely a function of market share and number of supply houses that carry the equipment.

Service teams: Larger contractors do, generally, have dedicated service teams. This advantage is eroded by the fact that PE-backed companies have incentivized their employees to sell you a replacement instead of fixing things.

I’d avoid PE-backed contractors, or the huge contractors here unless you’re the type of person who pays for a car’s extended warranty.

Mid-sized contractor with a few crews is where I personally consider the sweet spot to be, but I don’t have a clear recommendation here otherwise. When you’re vetting contractors, ask them who handles the service calls.

Conclusion

This is everything we know after a year’s work in the field. We’re choosing to publish it because we think you deserve transparency when it comes to knowing what quality actually means.

I’ve been in the room with HVAC salespeople who try to justify paying $10,000+ over market average

Because you’re paying for quality.

No, it’s because your company got bought out by Sila, which demands super high profit margins since it’s owned by Morgan Stanley (and now, Goldman Sachs) private equity.

Your choices in the world shouldn’t be between

Overpriced PE-owned HVAC conglomerate

Proverbial “2 Guys and a Truck4” contractor with no public profile

You should be able to find HVAC contractors who are high-quality, and also affordable. Finding, and pointing you to those contractors, is why we do what we do.

Furnace heat tends to be at a higher temperature, which means low airflow still delivers the same temp. Heat pumps deliver a more consistent, slightly lower temperature heat, which means you’ll need more air.

Appendix: Conversation w/Nate Adams, Industry Expert

I’m going to quote the great Nate Adams here, of Nate the House Whisperer, who has spent years going deep into the weeds on installation quality & building science.

This excerpt is from a Q&A he hosted on the MCJ Slack in February 2024:

Kit:

Let’s say you’re talking to a potential contractor.

What are the technical questions (besides a standard Manual J calc) you’d ask to ensure your installer correctly installs the equipment? (E.g. asking about commissioning, expecting an installer to know why it’s important to pull a vacuum below 500 microns)

Related to #1, for heat pumps that fail in under 5 years due to poor installation, what are the main mistakes that are made?

Nate:

For the first part, there are three big pieces to a good install:

Low duct pressure - the pressure inside the ducts should be as low as possible for fan life, compressor life, and coil life. The two easiest ways to reduce it are to downsize the equipment and to upsize the ductwork that connects to the unit, both supply and return.

Brazing with nitrogen - unitary split systems need to be connected in the field. Soot from brazing can add a lot of acid in the refrigerant which can substantially reduce compressor life. It's a simple fix: flow a few psi of nitrogen while brazing so soot can't get into the connections.

Deep vacuum - new refrigerant lines still have some contamination in them (water is a contaminant to refrigerant). The best way to get it out is to put it in a deep vacuum. Atmospheric pressure is about 750,000 microns. You for sure want to get below 500, preferably below 100 microns. That vaporizes contaminants and sucks them into the vacuum pump.

Those are 3 things to ask about when talking to contractors, and also critical install details. Not tackling those 3 could lead to constant equipment issues and failure in 5-10 years. Following those can lead to 15-20 year lives.One more key issue for installs: surge protection. Modern equipment is very sensitive to voltage fluctuations, so it's best to have a surge protector on both the indoor and the outdoor unit. The ICM493 is the consensus product for the outdoor unit.

Kit’s Response to #2:

I agree with everything Nate said, but I want to point out that some contractors are opting for pressing instead of brazing to connect refrigerant lines. We’ve heard that you can achieve a higher quality with a perfect braze, but press fitting is a lot harder to mess up, which means that the quality floor with press is higher.

Here’s the gold standard research from ASHRAE that confirms that press fitting is okay:

This is like, really building science-y, so we don’t anticipate every homeowner to ask about this. But we do vet our contractors against these things, and we won’t strike a bulk deal with a contractor until we’ve personally done walkthroughs at 2 or 3 installations, and ask them how they do their work/commission/etc.

Internal components are supplied by a lot of the same suppliers, anyway!

Side note: there is apparently an actual moving company called “2 Men and a Truck”. Legendary.