The Triple Decker Guide to Heat Pumps

The easy part, the hard part, and everything in between.

A Guide by Laminar Collective. We want to thank the Barr Foundation, via. the Building Electrification Accelerator, and Mass Save’s Community Education Grant for making this research possible.

We live in Cambridge.

And by we, I mean practically the whole team. I’m in Cambridge. Hannan is in Cambridge. Christin is in Cambridge.

You know what there are a lot of in Cambridge? Triple deckers.

They are iconic. Nothing says Camberville/Boston quite like a triple decker1.

This is everything we know about how heat pump design applies to triple deckers, and our approach from equipment selection to market pricing.

The Summary

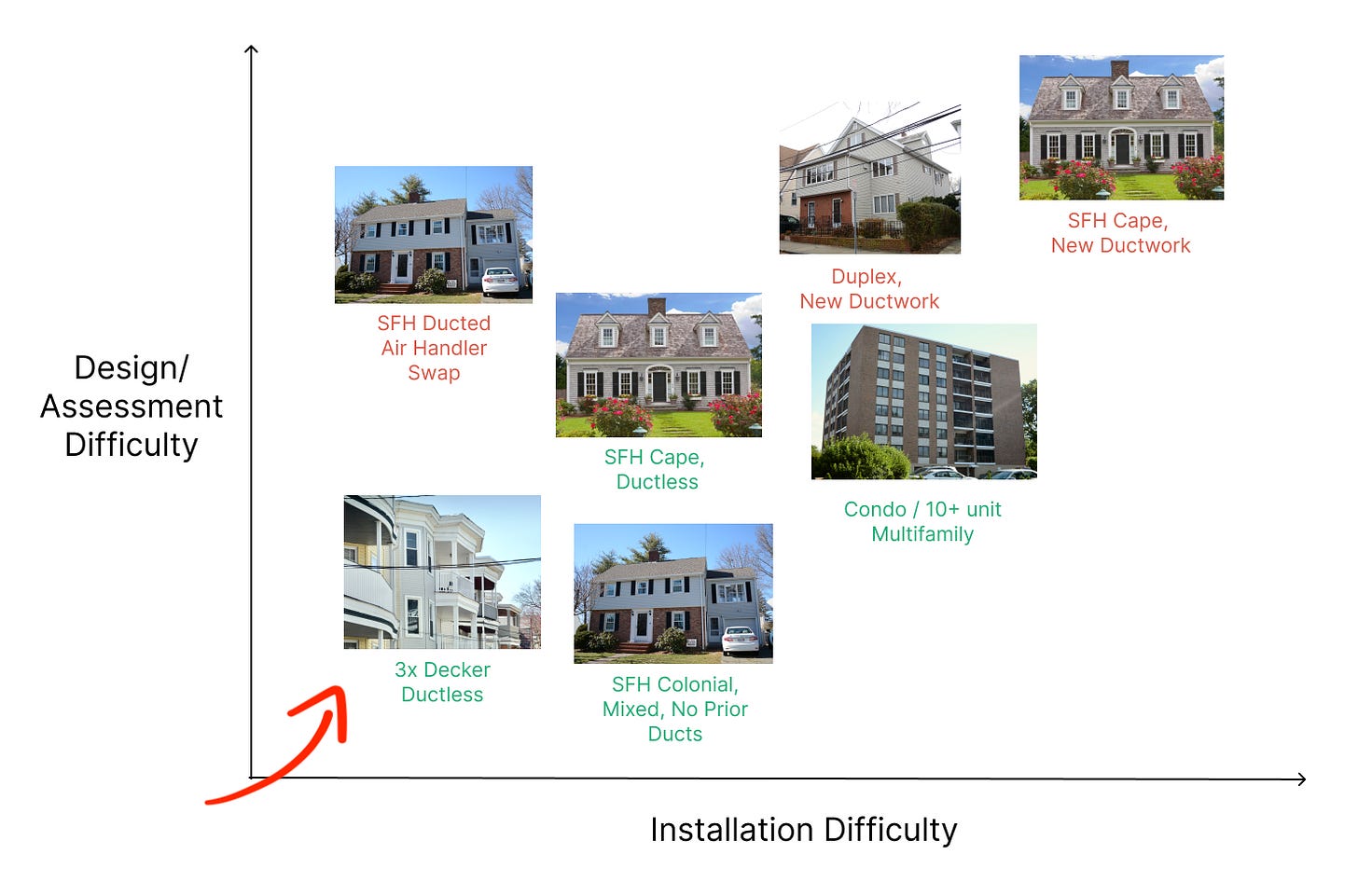

In the whole scheme of things, triple deckers are relatively straightforward installations, so you shouldn’t pay an extraordinary amount for them. Here’s how they rank in difficulty, on average, vs. other types of properties we see in the Boston Metro Area:

Here are the easy parts:

Most triple deckers don’t have ductwork, so ductless systems are usually the way to go. These tend to be easier to install than ducted systems.

Therefore, system design & equipment selection is usually super straightforward. Most contractors will align on the same solution2.

Exterior walls are usually very accessible, so refrigerant lines typically have an easy path to the wall unit. Most rooms will have an exterior wall.

Here are the hard parts:

Traffic and parking in urban locations usually more difficult vs. suburbs.

You might end up with an oversized system, especially in small 2nd floor rooms.

In select cases, you may need a 400 amp meter service upgrade for the whole building. If you live/own a single floor, it can be difficult to get your neighbors to help chip in for this upgrade.

Space constraints between neighbors + long line runs to 3rd floors.

If you don’t need a 400 amp service upgrade, or have a weird edge case (e.g. Victorian exterior 3rd floor soffit we need to punch through), we think you can get a reliable installation for about ~$5,000 per head for most of the year outside of summer.

Standard Layouts

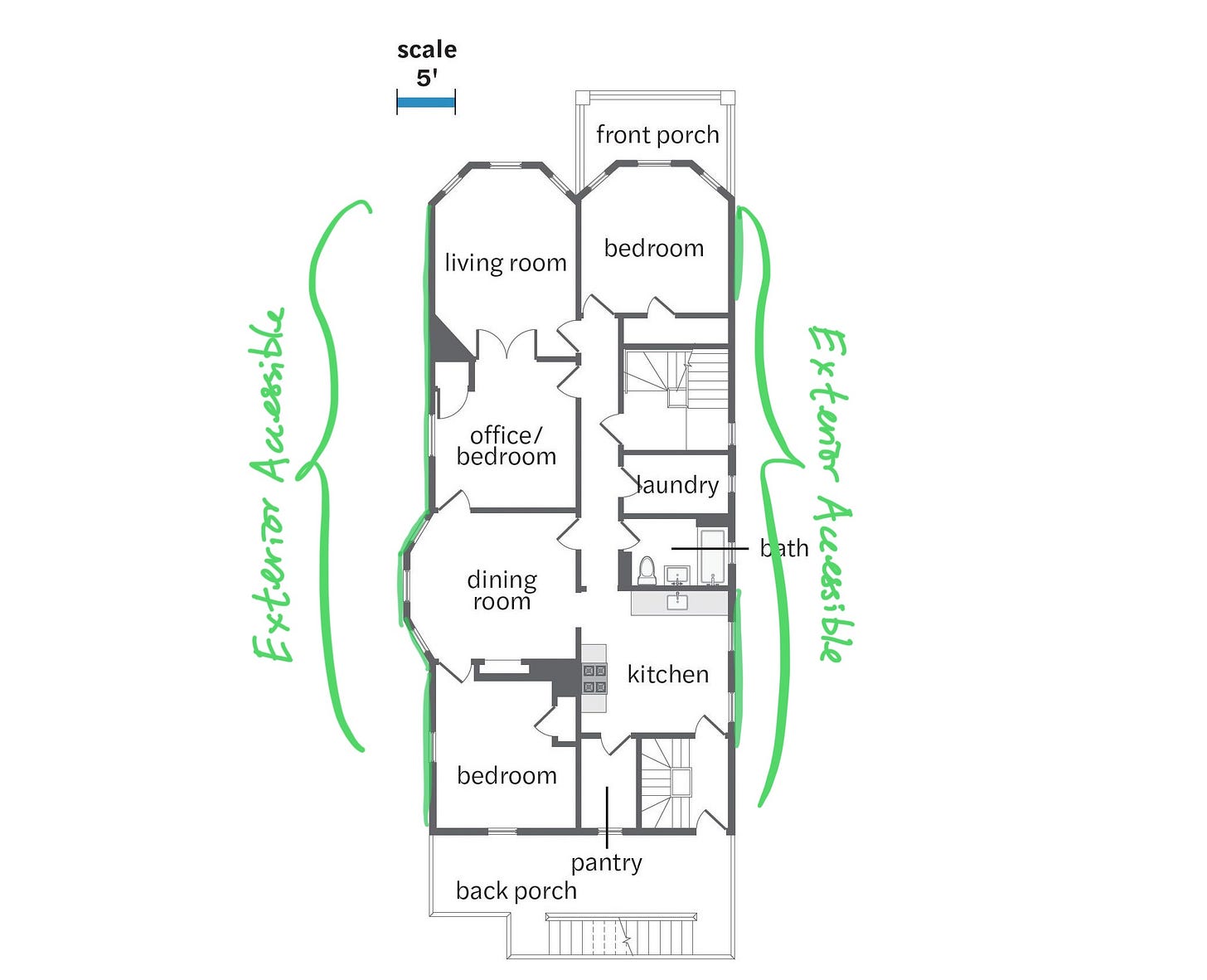

Each floor of a triple decker is usually an independent unit, mostly identical to the other floors. Square footage can range from 850 ft² to 1250 ft².

Two common designs are:

2 bedroom unit: typically 4 heating zones (each bedroom + kitchen & living room)

3 bedroom unit: typically 5 heating zones (each bedroom + kitchen & living room)

Sometimes, the kitchen & living room is one open space, and in that case, we may have n+1 heating zones instead of the n+2 heating zones above (where n = # of bedrooms).

In most cases, each important room will have an external-facing wall:

This matters because it makes it much easier to vertically run refrigerant lines up the face of a side wall, right up to the location where a wall unit may be mounted:

Ultimately, this makes life easier because in most cases, we’re just running a line straight up a wall. But how do we get refrigerant lines to both sides of the house?

Design Considerations

Line Runs. To get to every single room, you’ll need to access both sides of a house with minimal aesthetic impact. But typically, the condenser (outdoor unit) is only on one side of the house to start with. How do we get to the other side?

One common method to get to the side of the house opposite of a condenser is to run lines across the basement (since there’s no real attic).

Most basements are partially above ground, so you can drill a hole like this one to access the basement:

From these access points, you can directly run lines from one side to the other, then up to the rooms where they need to be.

Ductwork. If you don’t have pre-existing ductwork, it’s going to be a major hassle figuring out how to install it. Most homes with ductwork have some sort of empty attic or basement space above/below the finished units. That’s not the case with triple deckers, perhaps with the notable exception of the 1st floor (and that’s before we get into questions of basement ownership).

Expect a major renovation if you want to go this route for the 2nd or 3rd floor.

Heat Loss. The top floor will lose more heat because the ceiling is exposed to the elements. The middle floor will require the least because it’s sandwiched between two conditioned spaces.

Here’s the heat load required for 3 floors of the 1910s, recently insulated triple decker you saw earlier (calculated & verified by Abode):

Unit 3

Heating 26,000 BTU

Cooling 11,000 BTU

Unit 2

Heating 16,000 BTU

Cooling 9,000 BTU

Unit 1

Heating 18,000 BTU

Cooling 10,000 BTU

As you can see, heating loads range from 16,000 BTU to 26,000 BTU. Remember these numbers. We’ll have to select the appropriate equipment that matches that load.

Sizing & Equipment Selection

The goal of proper sizing is to get as close to that heating load as possible, while not going way over. Oversizing = more expensive. We assume the house is weatherized3.

Condenser Selection. First of all, you’ll want to select a cold climate model that retains ~100% of heating capacity at 5°F, and capable of heating at reduced capacity into the negatives.

Assuming you’re selecting a cold climate condenser, it turns out that if your heating load ranges from 16,000 BTU to 26,000 BTU, even the smallest capacity condensers for 4 ports/zones/wall units has enough heating output to comfortably heat a triple decker unit:

Pay attention to that minimum heating BTU column. Thanks to inverter/variable speed compressors, all of these models can modulate heating output between the max & min BTU values.

Every single brand listed here comfortably heats between 16,000 BTU to 26,000 BTU.

This means that equipment selection is simple4. Just pick the smallest condenser available for your number of zones, and back that up with a Manual J load calculation to confirm.

Oversizing Risk

You’ll notice that Mitsubishi’s 4-port model has the highest min. heating output, at 22,500 BTU:

This is fine for spacious 3rd floor units, which are a lot more exposed (exterior ceiling), but for a 2nd floor unit that’s sandwiched between 2 conditioned floors that only needs 16,000 BTU at most5, we prefer going with a model that has a better turndown ratio.

Oversizing leads to inefficiency during the shoulder seasons6. But Mitsubishi does have something else going for it: high efficiency ratings.

Efficiency Ratings

Let’s talk about efficiency. We’re talking about SEER and HSPF, which correspond to cooling & heating efficiency, respectively:

From a raw performance standpoint, Mitsubishi comes out on top - so it’s justified for contractors to speak so highly of the brand. But Daikin is close behind, and doesn’t have the same turndown issue that Mitsubishi has. For that reason, I’d say they’re on par, with Fujitsu, Samsung, and LG coming in slightly behind (for performance & other reasons7).

This is an opportunity to save money without compromising on performance.

What about using 2 condensers?

I think this is a nice-to-have, not a need-to-have.

Pros: better performance, solves the turndown ratio problem for Mitsubishi, redundant system means if one fails, you’ll still have another

Cons: more expensive, takes up limited space on lot b/c you need 2 condensers

Sizing-wise, you’ll almost always end up with more heating capacity than you need. Just pick the smallest possible condensers. This is a good option for 5 zones, and the preferred option if you have 6 zones.

Installation Process

A single unit, 1st or 2nd floor installation takes ~3 days, give or take.

Here’s an approximate 3 day schedule for a ~2 person crew + electrician, who works concurrently on the final day:

Initial walkthrough, equipment arrival (1 hour)

Mounting indoor units up on wall / drilling exterior holes, incl. basement (0.5 day)

Running refrigerant lines & line cover, wiring mini-splits (1 day)

Mounting condenser, vacuum pressure testing, charging refrigerant (1 day)

Wiring to electrical panel, done simultaneously by electrician (0.5 day)

Final commissioning run (1 hour)

Demolition of prior system (2 hours)

Additional complexities, such as running lines up to the 3rd floor, dealing with horsehair plaster, or exterior soffits will add time.

Electrifying an entire triple decker will take about 10 to 12 days, depending on difficulty. If you bump up the crew size, you may be able to get it done faster.

Market Pricing & Cost Breakdown

Baseline Pricing

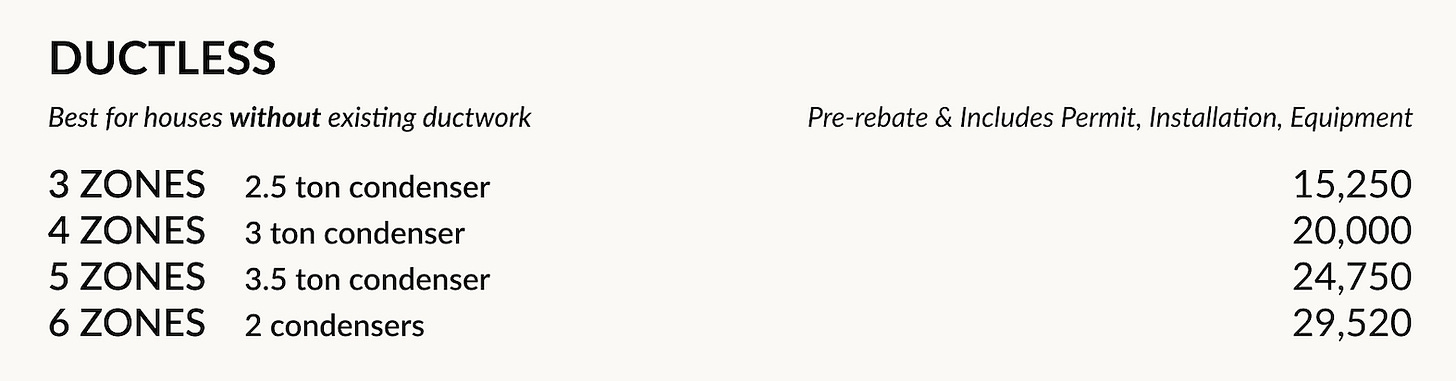

There is a wide range of prices that you’ll find for installations in the market. As for what a good price is for a relatively simple, high-quality installation? I’d say it looks something like this:

These are prices that we’ve negotiated for our prior bulk deals, and the prices that we’re aiming to maintain through 2025. It roughly corresponds to ~$5,000 per zone, post-permit. We think this is a good reflection of the prices you can achieve from some smaller, leaner contractors (who don’t have a ton of overhead).

Cost Breakdown

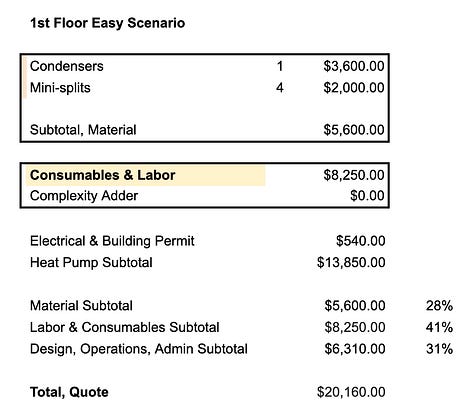

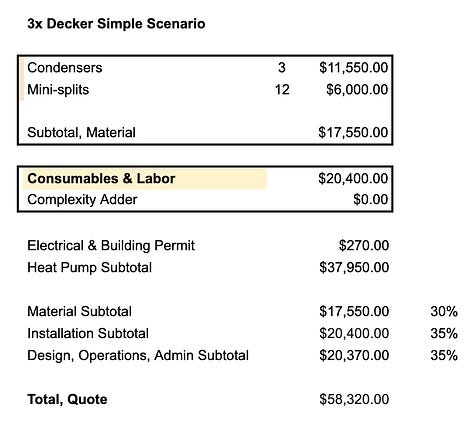

Let’s take a look at 3 different installations:

Easy 1st floor 4-zone scenario

Difficult 3rd floor 4-zone scenario

Easy-ish triple decker scenario, which is essentially #1 for all 3 floors

Here’s what the breakdown8 may look like:

Of course, this may be different for other contractors. Let’s say you’re a contractor who decided to buy a massive warehouse or office for some reason. Guess what? Your operations & admin costs will go way up.

Reasons Costs May Be Higher

Complex installations. Cost is higher, and additional revenue typically gets allocated to labor & consumables, due to the additional labor hours required & additional consumables (e.g. longer refrigerant lines, more refrigerant).

Contractors who want to charge a higher margin, for whatever reason9. Sometimes it’s fair (big service team), other times it’s not (owned by PE).

Here are some common complexity adders for triple deckers:

And here’s where that money goes:

For us, we believe labor & consumables should be between the mid-30s and the mid-40s, because installation technicians deserve to get paid well. Well-paid technicians typically do better installations. And we believe in high-quality installations.

Seasonality

Prices tend to be highest during the summer. 10% commission seems to be industry standard for HVAC salespeople, and during the peak summer season they tend to charge more. Conversely, you get the most negotiating leverage from January through April.

We personally don’t like the commissions-driven sales model (or salespeople trying to upsell you), and that’s partly why I negotiate the rates on behalf of consumers. But more on that later.

Rebates

Mass Save offers a $3,000/ton rebate per triple decker unit, maxing out at $10,000. Considering the rated capacity of each model, you’d likely receive anywhere between 2.5 x $3,000 = $7,500 to 3 x $3,000 = $9,000 in rebates.

Beware: there are probably HVAC salespeople out there who will want to upsize your system to 3.5 tons to max out the $10,000 rebate limit. Don’t do it.

But Wait. Will I Save Money Heating?

Most of Cambridge, Somerville, and Boston heat with natural gas. Truthfully, in January 2025, heating with a heat pump will cost slightly (~10%, on average) more expensive than heating with natural gas10.

So, chances are, the main benefit of a heat pump this year is AC, comfort, and getting ~$9k in rebates.

Conclusion

There are 3 important takeaways here:

System design & equipment selection is fairly simple for a triple decker, which makes it easy to generate a fairly accurate estimate.

Installation is fairly straightforward as well due to easy access to exterior walls, unless you’re dealing with exterior soffits, 3rd floor, or horsehair.

Mitsubishi doesn’t have as much of a lead for triple deckers as it does for larger units, while it’s usually priced thousands more.

My advice? Don’t overpay. Unless you run into something like a 400 amp electrical service upgrade, triple deckers are typically more straightforward.

Here are the pricing targets we are negotiating for the spring. If you’d like to access them, sign up on Laminar Collective.

A Personal Note

Laminar Collective’s mission is to make heat pumps more accessible to the mass market by lowering costs, and I have spent 1.5 years of my life in pursuit of every possible way we can lower costs without compromising on quality.

I hope you recognize that this article took a realllly long time to write. We are spending months on this (plus benchmarks, plus installation visits in 10°F!) and it is a lot. We’re publishing this for free because we care about consumers, and we want consumers to make good decisions.

Want to thank us?

Sign up for Laminar Collective & participate in a bulk deal

Sharing our guides with your friends & enemies (we’ll have other homes soon!)

Get an estimate from Manatee (if you’re in Cambridge, Somerville, nearby Boston Metro!), a software platform we built precisely on analysis like what you’re seeing on this article

Doing so helps us make money so we can help even more people / or else we stop.

Alright, that’s all from me. Thank you all for being a part of our little, tiny research collective here at LC :)

Afterword

Special shoutout here to MassCEC, who’s running a Triple Decker Design Challenge. They’re going to publish a few specific case studies (one of which we’ve done an installation for!), and when that’s ready, I’ll publish their article here so you have another data point. We didn’t receive funding from MassCEC, but we appreciate the research work they do.

They’re also wildly expensive, but we will save that conversation for another day.

Cape houses, on the other hand, are quite difficult to design for.

You’ll need to get this weatherization done if you want a heat pump rebate anyway, so we’re assuming that the house will be insulated to at least Mass Save standards.

This is why we can usually give you an estimate for a triple decker installation virtually.

During the shoulder seasons, you don’t need 16,000 BTU.

Snippet from this great Green Building Advisors article. Manual J numbers reflect the most extreme days of the year, while in the shoulder seasons (e.g. November) you won’t need that much:

Winter: 99% design temperature. This is the outdoor temperature that your locations stays above for 99% of all the hours in the year, based on a 30-year average. Turning it around, the outdoor air where you live is going to be colder than this temperature for only 1% of the hours in a year. That happens to be about 88 hours per year. In Atlanta, the 99% winter design temperature is 23°F.

Summer: 1% design temperature. Your location will go above this temperature only 1% of the hours in a year, again, based on a 30-year average. Here in Atlanta, that number is 91°F, so we go above that temperature for only about 88 hours in a year.

Fujitsu just got acquired, so I’m not 100% sure how that’ll shake out yet in terms of parts availability. Plus, Fujitsu has a 12,000 BTU min capacity, which is okay but not as good as Daikin’s.

Meanwhile, Daikin is building a significant distribution network in the Northeast with the ABCO acquisition (one big supply house is in Somerville, right next to Assembly Square!). LG holds their market share, and I’m just not seeing that much Samsung in the Northeast right now. Need to dig in more on parts/supplier availability for Samsung.

December 2023, I told a friend that I’d pay good money to see the books because HVAC contractors NEVER give you a breakdown. Well, readers, we did it. We started a whole damn company doing research installations to do it.

PE-owned companies. If your company got bought out by Sila, which in turn is owned by Morgan Stanley private equity, the share going to Profit goes WAY up.

Huge contractors. If there are like, 20 crews, the additional facility cost for an office, warehouse, operations contributes to higher overhead.

Contractors trying to scale. Maybe a contractor wants to scale, and is bootstrapping from proceeds from jobs. Sometimes they’ll charge higher to make more margin, so they can hire more people.

Salesperson trying to make more money. HVAC salespeople range from the truly technical & capable, to a live representation of a sales seminar. They typically make 10% commission from you, so they’re going to usually try to establish as much “value” as possible to make you pay more, so they make more money.

LC reader Natalie notes that towns may have municipal aggregated electricity rates that are a bit less than Eversource & National Grid.

Not mentioned in this article is that if you are a landlord and 50% or more of the households in your building are on fuel assistance or on a reduced electrical rate this work is NO COST (free) through Mass Save's income-eligible program. For a triple decker, that means at least 2 of the households need to be on fuel assistance or reduced energy rate. For this to be done you need to get an energy assessment and the heating system has to be old and need of replacement (unless it is resistant electric and then it can automatically be replaced with heat pumps). If you heat with oil or propane the system must be nearing its end of life. They might give you push back if you want to replace an old natural gas system, but you can replace natural gas with heat pumps if the heating system is over 12 years old, but you need to advocate for it. By the way, the same rules apply even if the building is owner-occupied (landlord lives in one of the units.) If you have any questions you can contact savegreen@capeannclimatecoalition.org, we have a grant from the Mass Clean Energy Center to help landlords/renters through through the income-eligible process on Cape Ann (Gloucester area), and we can help answer any of you questions or concerns.